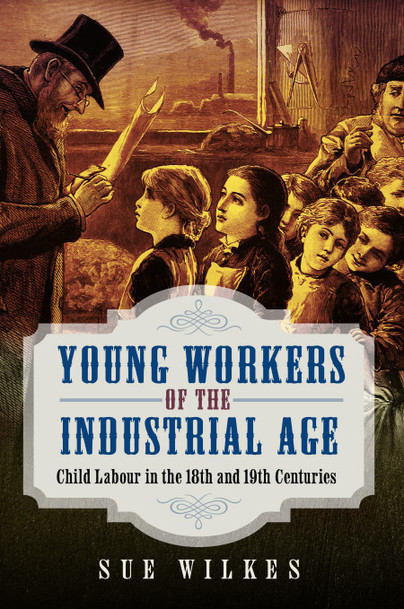

Young Workers of the Industrial Age (Hardback)

Child Labour in the 18th and 19th Centuries

Imprint: Pen & Sword History

Pages: 272

Illustrations: 32 mono illustrations

ISBN: 9781036113834

Published: 4th October 2024

(click here for international delivery rates)

Order within the next 6 hours, 5 minutes to get your order processed the next working day!

Need a currency converter? Check XE.com for live rates

| Other formats available | Price |

|---|---|

| Young Workers of the Industrial… ePub (16.6 MB) Add to Basket | £14.99 |

The industrial revolution was forged with the lives of our ancestors’ children.

All over Britain, children and young people toiled for hours every day. Their workplaces were pitch-dark mines, fiery furnaces, brightly-lit mills with deadly machines, and mud-filled brickyards.

Some workers were pauper apprentices, sent thousands of miles from their homes and indentured until the age of twenty-one.

Almost every item in our ancestors’ homes and wardrobes was made by children and youngsters: buttons, glass, carpets, cotton, cutlery, pins, candles, lace, pottery, straw hats, and even matches.

In grand houses and ordinary homes, tiny chimney sweeps climbed chimneys choked with soot, and boys and girls worked as domestic servants. On the land, both sexes worked in all weathers. Children worked at home, too – many helped their parents earn a living.

From the early 1800s, men like Robert Owen tried to improve children’s lives. But reform was held back for decades by wealthy mill-owners, landowners and politicians who believed that profits were more important than people.

Sue Wilkes tells the story of the battle for workplace and educational reforms led by Lord Shaftesbury, Richard Oastler, and the indefatigable factory inspectors. But it took many decades to transform society’s attitude towards childhood itself.

Young Workers of the Industrial Age takes a fresh look at the childhoods stolen to create Britain’s industrial empire.

Rating: 5 out of 5 stars

NetGalley, Robin Joyce

This is a harrowing account of child workers, and their occupations, in the 18th and 19th centuries. I found it impossible to read at one sitting, not because of the style (as usual in these publications it is eminently readable) but because of the inhumanity it brought so graphically to life. Equally, Wilkes’ attention to the philosophy behind the treatment of children in that period is distressing – after all, are the ideas behind punishment for poverty so removed from current circumstances? Then profits rather than people were considered of utmost importance. Wilkes leaves us with the question - and now? It is Sue Wilkes’ empathy with the workers and her enlightening discussion that makes this book powerful, and I reiterate, harrowing. However, this does not mean it should not be read. Although aware of the circumstances under which children laboured from other sources, Wilkes’ research is commendable, bringing as it does such detailed accounts of the occupations and conditions that endured in this period.

That children’s labour provided to those who could afford them, clothing items such as cotton, buttons, pins, lace, and straw hats is graphically described. Further, the point is made that children also produced household items such as glass, carpets, cutlery candles and pottery and swept the chimneys of these houses – again, for those who could afford them. That the houses warmed with these soot laden structures, above fires with matches that child labour produced, were cleaned by young people, for many hours a day becomes real under Wilkes’ hand. Reading this book, it is now less difficult to picture the well clad people that we see in film and on television in period dramas taking advantage of the philosophy around children and childhood in the period.

Legislation, often the outcome of the realisation that education was important, made some minor inroads into the hours children worked. And here, Wilkes again makes the point that the compromises reached were attendant on industries’ changing needs. An empire in which children could contribute as educated beings as well as through work was gradually being recognised, for some in power because of compassion, for others because the economics of industry and political power in a changing world had changed.

There are illustrations which are described in detail; an extensive bibliography, including contemporary works such as newspapers, and pamphlets; reports, such as those relating the outcomes of various commissions and inspectors’ reports; journal articles; and a copious number of books; an index and detailed notes related to each chapter. Various occupations are the subject of museums, and the details of these are provided. There is a timeline of legislation - another valuable resource.

This is a book is a must read for anyone who is curious about the plight of children in the industrial age and the lengths the world went to offer a better life for children of today.

NetGalley, Abigail Tyn

Rating: 5 out of 5 stars

NetGalley, Colin Edwards

This is an excellent book. Although it’s crowded with mentions of Acts of Parliament; with names of heroes and villains (and the children); and with statistics, it is never too dry. The changing focus upon one industry, then another, keeps the reader’s attention. This is not a comfortable subject – one’s heart bleeds when reading the tales of exploitation and cruelty – but it is a must-read for anyone interested in social- or labour-history.

Rating: 5 out of 5 stars

NetGalley, A D

From education I remember learning about children in workhouses and what type of work they did but this book gave me a much more detailed and interesting account of the truth of child workers during this time.

Very insightful with a great deal of detail on relevant laws of the time, as well as moving case studies of individual experiences. The author did a wonderful job of making this engaging and easy to read while also imparting deep research. A great addition to the social history of the period.

NetGalley, Louise Gray

Rating: 5 out of 5 stars

NetGalley, Pippa Elliott

The content is shocking at times but the author’s style is highly readable. It is a detailed, factual account of how small victories over the decades led to change. A true account of evolution rather than revolution. I can heartily recommend it.

Well-written and highly readable, this is not simply a sad story about the past and children’s place in it, important as that is. It’s also a reminder that we shouldn’t be too smug. Maybe our children can go to school and play instead of working for wages. But for many children, the whole idea of such a childhood is still out of reach, even in the 21st century.

NetGalley, Cynthia Comacchio

About Sue Wilkes

Sue Wilkes is a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society. She has written extensively on social history, and industrial history and heritage. Sue was born in Lancashire, and has lived in Cheshire since the early 1980s. She read Physics at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford. Sue is married, with two grown-up children.

She is the author of nine books and is a well-known family historian. A regular contributor to Jane Austen’s Regency World for over two decades, Sue has written many articles for history and family history magazines such Who Do You Think You Are?. She loves exploring Britain’s history and heritage, and is a keen gardener.