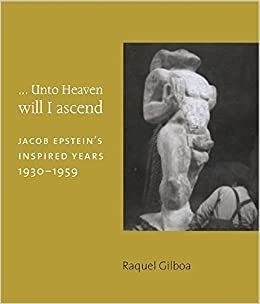

... Unto Heaven Will I Ascend (Paperback)

(click here for international delivery rates)

Need a currency converter? Check XE.com for live rates

As an American living in England, a conscious Jew who utilized Christian symbols, a skillful modeler who introduced direct carving into England, and a modernist who eventually came to dislike abstraction for its own sake, Epstein did not fit neatly into the artistic categories of his time. Apart from his still widely admired naturalistic bronze portraits, Epstein’s oeuvre remains poorly understood and his reputation is dominated by his famous Rock Drill from before World War I. As this book shows, Epstein remained an avant-garde artist throughout his life, even if he ignored modernist dogma as well as man-in-the-street prudery. Gilboa’s text reveals the man in all his genius, interpreting many works in the light of Epstein’s personal circumstances.In an atmosphere of polarized attitudes to art and polite anti-Semitism at the end of the 1920s growing rather less polite thereafter, the outsider Jew Epstein deliberately became estranged from London’s art world. He responded to society’s attitude towards him in a series of bold projects – the monumental Genesis (1930) and Primeval Gods (1931–32); the smaller carvings Chimera and Elemental (1932); Behold the Man (1934–35); Consummatum Est (1938–39); Adam (1938) and Jacob and the Angel (1940); the bronze Lucifer (1944–45) and again a carving, Lazarus (1947). One cannot ignore the symbolic names of these sculptures. The discussion in this book will reveal that in each case the name has a definite relation to the sculpture’s theme and essence, as well as to the personal concerns of the sculptor.Almost all of these sculptures that Epstein produced from the 1930s aroused a public outcry, causing one critic to state that “a new carving by Mr. Epstein – good, bad or indifferent – can still steal the headlines when criminal assault, private or political, is out of season”. It was only during the 1950s, following the trauma and emotional shock of World War II, that new requirements for the expression of ideas and emotions rather than for mere forms with which to play renewed the demand for ‘an Epstein’ and his kind of ‘content’ sculpture, mainly in public commissions. Epstein, by then in his seventies, was flooded with work, and his sculpture – which employed Christian imagery to convey universal ideas of consolation and hope to a war-weary England – became newly relevant, gaining him the status of grand old master of English sculpture.