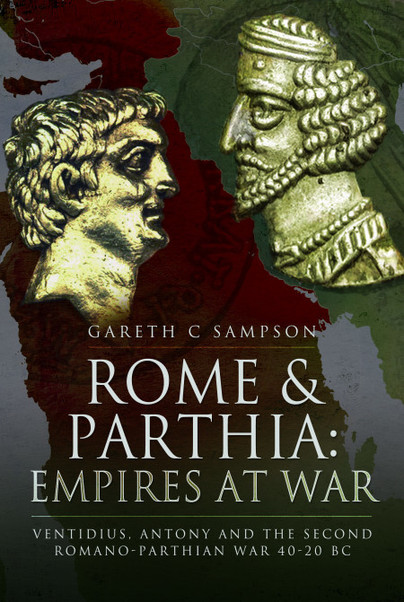

Rome and Parthia: Empires at War (Paperback)

Ventidius, Antony and the Second Romano-Parthian War, 40-20 BC

Imprint: Pen & Sword Military

Pages: 344

Illustrations: 20 illustrations

ISBN: 9781399002875

Published: 9th November 2021

(click here for international delivery rates)

Order within the next 2 hours, 23 minutes to get your order processed the next working day!

Need a currency converter? Check XE.com for live rates

| Other formats available | Price |

|---|---|

| Rome and Parthia: Empires at War ePub (16.5 MB) Add to Basket | £6.99 |

In the mid-first century BC, despite its military victories elsewhere, the Roman Empire faced a rival power in the east; the Parthian Empire. The first war between two superpowers of the ancient world had resulted in the total defeat of Rome and the death of Marcus Crassus. When Rome collapsed into Civil War in the 40s BC, the Parthians took the opportunity to invade and conquer the Middle East and drive Rome back into Europe. What followed was two decades of war which saw victories and defeats on both sides. The Romans were finally able to gain a victory over the Parthians thanks to the great, but now neglected, general Publius Ventidius. These victories acted as a springboard for Marc Antony’s plans to conquer the Parthian Empire, which ended in ignominious defeat. Gareth Sampson analyses the military campaigns and the various battles between the two superpowers of the ancient world and the war which defined the shape and division of the Middle East for the next 650 years.

Roman history has always fascinated me, having struggled through Gibbon’s classic “ “Decline and Fall” in my misspent youth and I have enjoyed gaming their exploits, particularly against the Carthaginians. Somehow their Civil Wars didn’t quite catch my interest as much, but recently I read a book that did peak my interest: Gareth Sampson’s Rome & Parthia: Empires at War: Ventidius, Antony and the second Romano-Parthian War 40-20 BC. (Pen & Sword, 2020).

John D. Burtt

The story takes place essentially in Asia Minor and the Middle East, where the two empires fought for control, going back and forth in an ancient version of World War II’s North African campaign. What makes it more interesting is that both empires fought this war while dealing with internal civil disturbances. The Parthians (along with an anti-Rome Roman), swept into Rome’s Asian provinces while Rome dealt with the backlash of their Civil War which marked the start of the second major conflict between the empires.

Sampson’s task is not particularly easy; Roman history is pretty well known and documented, while the Parthian Empire which originated east of the Caspian Sea certainly isn’t. As he put is, “the Parthian Empire lasted for 470 years…and we have a ridiculously small amount of surviving material about it.” (pg 275) As such Sampson can only guess at some of the internals of that Empire, but those internals appear pretty standard for the period. Kings leaves “trusted” advisors behind while they campaign; trusted advisors then rise up behind them. Or, as happened in the first Romano-Parthian conflict that ended at the battle of Carrhae, the victorious Parthian general, Surenas, was almost immediately executed by a jealous monarch. He has added an appendix detailing what sources about Parthia are available.

The book has a modern bite to it, especially when comparing it to events during the cold war. The statement “Herodes may have been declared the King of Judea by the Romans, but installing in in Jerusalem was another matter,” (Pg 138) reminded me of the leaders installed and supported by both sides in the cold war, based solely on their anti-otherside support. Much of the provinces throughout this period became very tired of trying to pick the ‘winners” in these internecine shenanigans, trying to stay neutral as opposing armies and fortunes swept to and fro over them.

A warning about this book, though. Trying to maintain who was doing what to whom can tend to get confusing especially when leaders have the same name: Mithradates, for example was the name of a leader of a Parthian, a Pontic and a Bosphoran King during this period. Despite that, you can follow his narrative fairly easily, aided by several maps that delineate the various provinces and empires as they grew, changed hands and shrank.

Despite the lack of hard facts (no one knows, for example how many troops Parthian leader Pacorus had with him in the initial assault on the Roman Asian provinces) the narrative is a compelling look at two empires in the throes of internal troubles attempting still to expand.

Sampson tells an engaging and balanced story of two major powers slugging it out and the minor powers caught between them; all of which takes place in the chaotic collapse of the Roman Republic and various Parthian civil wars. The narrative is slanted to the Romans because of the lack of sources on the Parthian side, but Sampson winkles out what he can and makes educated guesses where he hits blank spaces. He also incorporates many of the sources into the narrative... this is a first rate military history of an often confusing theatre of war.

Beating Tsundoku

Read the full review here

“…a useful book for a general audience, with excellent narratives of events on the ground and much analysis of evidence that is convincing, to varying degrees. [T]he audience will certainly come away with a better understanding of the frontier policies and goals of Mark Antony, his allies, his subordinates, and his enemies.”

Bryn Mawr Classical Review

Read the full review here

This is an excellent account of this relatively unfamiliar war, combined with a useful history of the Roman East in troubled times.

History of War

Read the full review here

A good read for those interested in Roman history, and particularly for Sampson's "rescue" of Ventidius from obscurity.

The NYMAS Review, Winter 2020-2021

A very interesting read, entertaining as well as being very informative.

Army Rumour Service (ARRSE)

Read the full review here

This marvellous book provides much needed information on a little-known period of Roman Empire history.

Books Monthly

About Gareth C Sampson

After a career in corporate finance, Gareth C Sampson returned to the study of ancient Rome and gained his PhD from the University of Manchester, where he taught for a number of years. He now lives in Plymouth with his wife and children.