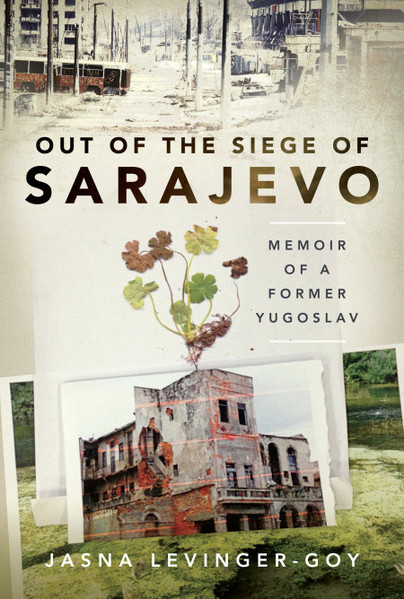

Out of the Siege of Sarajevo (ePub)

Memoirs of a Former Yugoslav

Imprint: Pen & Sword Military

File Size: 8.4 MB (.epub)

ISBN: 9781399098632

Published: 30th January 2022

| Other formats available - Buy the Hardback and get the eBook for £1.99! | Price |

|---|---|

| Out of the Siege of Sarajevo Hardback Add to Basket | £20.00 |

The horrors of the civil war in Bosnia and Herzegovina, in the very heart of Europe in 1992, may be all but forgotten – but not by everyone. In this book, Jasna Levinger-Goy offers a vivid, personal story of a family of Jewish origin who identified as Yugoslavs. It traces their journey over a period of ten years, starting with their life in Sarajevo under siege and ending in the United Kingdom.

Without belonging to any of the warring factions, this is Levinger-Goy's true story, a story that takes place on the front lines in the heart of Sarajevo. The book offers a percipient view of the civil war through the eyes of those who witnessed it. We are presented here with the motives, reactions and behaviour of people caught in the crossfire of political and military events outside their control. It illustrates coping with dangers and the resourcefulness needed during the siege and during the perilous journey out. It also shows that almost the equal amount of coping mechanism and resourcefulness was required in adapting to new circumstances as well as in building a new life.

Levinger-Goy’s venture into the unknown is tangled with the sense of loss – of home, of a country and the loss of identity. Her experience provides an insightful commentary on how these intersect, overlap and ultimately affect an individual. It sheds light on human suffering and resilience, frailty and ingenuity, cruelty and empathy. It describes unique personal circumstances, but illustrates universal behaviours. Although the book inevitably deals with fear, pain, desperation, loss, and even hatred, it also reveals much about love, hope and happiness and above all about the prevalence of good even in the most difficult of circumstances.

Set against the backdrop of a brutal conflict, this book reminds us of the very human cost of war.

Article

Gordana Lalic-Krstin, НАСЛЕЂЕ 59, ČASOPIS ZA KNJIŽEVNOST, JEZIK, UMETNOST I KULTURU, Journal of Language, Literature, Arts and Culture, YEAR XXI / VOLUME / 59 / 2024

Highlight: 'The book provides the most detailed account of the period of about ten years, from the beginning of the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1992 to around 2002. …..Among other things, it includes the theme of identity, its loss and rediscovery; the theme of language and its role as one of the most important identity markers, but also as a medium and mediator through which we establish relationships with events; the theme of memory and its subjectivity and unreliability; and, finally, the theme of collective and personal trauma and its overcoming.

….

One of the central themes of the book is the question of identity: national, ethnic, linguistic, religious, social, professional, and personal. With the outbreak of war, everything the author had been and the way she perceived herself disappeared overnight. However, it would be incorrect to say she lost her old identity—it was taken away, abolished, forcibly dismantled.

……

Language, alongside identity, is another major theme of the book. Language serves as a medium for relating to one’s experiences, a carrier of memories, and a mediator through which we understand, remember, and feel. It allows us to immerse ourselves in our emotions, awaken those we have repressed, but also to distance ourselves and analyse them from the safety of a foreign language.

……

This is not a book about war, yet it is very much a book about war, as are all personal histories of those whose lives were swept up in the whirlwind of the Yugoslav civil war in the 1990s. It is, as the author states, just one story from one cellar. And there were many cellars in those years, as we unfortunately know all too well—cellar as physical spaces, as metaphors, as locations, and as states of being. … These stories must be retold so they are not forgotten. Jasna Levinger-Goy has told her story—let’s hope someone is listening.

'

English Translation:

Bozidar Stanisic, Osservatorio

The book was first published in English: Out of the Siege of Sarajevo: Memoir of a Former Yugoslav (Pen & Sword Military, Yorkshire - Philadelphia, 2022). Subsequently Jasna Levinger-Goy translated her own book into Serbo-Croat making some not substantial alterations. In her foreword she states: “For English readers my text is a testimony of recent historic events in a “faraway” country, while for domestic readers (…) the books serves as a reminder of the events whose echoes are both relevant and still present in the mind of many people.”

Her book – an unrelenting testimony of Sarajevo under siege, mercilessly describes the fate of others as well as her own throughout the drama (as well as irony) of a particular moment in history, still unresolved.

However, it is far from ever dominant and widespread black-and-white narratives describing the siege of Sarajevo (1992-1995).

I would happily both start and end my review of Jasna Levinger-Goy’s memories with the above sentence. I would much rather include more of the fragments from the book itself. I would possibly only mention the fact that it might be “interesting” to read first the Appendix A at the end of the book. But this would simply be a recommendation, not only for the readers from the region but rather from Europe as well.

The Appendix A full of brief, sometimes laconic, indications regarding the dispersal of people and their fate reminded me of the fact that as far back as the Greek and Roman times people understood that in every war and in every adversity individuals and their destiny were very much like a leaf in the wind. Yes, indeed every one of us could write such a testimony but very few had done. However, as far as I know, among the plethora of personal accounts I have read so far, nobody has done it. I have stopped reading those books now. Yet I keep wondering why all those people belonging to either warring party in the Yugo-tragedy pretend to bear witness of the time while actually painting the picture of themselves only, talk about their suffering and their pain only (not to mention the hatred and intolerance of their own side which is often clumsily concealed.)

Out of the Siege of Sarajevo is certainly not one of those books. Definitely not, since Jasna Levinger-Goy talks about others even when she talks about herself. On top of that the author of this book belongs to neither of the three warring parties in the Bosnian civil war (and that too distinguishes hers from the common narrative). She was on the forth side, the side of the people who realised that by losing Yugoslavia as the only real homeland they had forever lost one important ingredient of their identity. Hence, she was a looser, and a Jew at that, who inevitably went through several visceral and cerebral stages: from disbelief and surprise at the unfolding events, to realisation of the cruelty of the reality of war and its horrors to a fleeting thought that evil dominates, but concluding with the experience of good, of meeting noble people everywhere. That brought forward her need to tell the story, to offer a true account of everything she saw or went through. Good people in this book shine the light on hope and the dominance of good. The reader will easily recognise Jasna Levinger-Goy’s view of people who turned evil: there is no word of condemnation, there is only astonishment at this sudden and unexpected transformation.

This book is predominantly an illustration of the life of a Jewish family in the besieged town. Where is society better reflected than within a family? (In The Novel about London Crnjanski states “to learn about humanity one does not need to know the entire humanity. Getting to know one family well would suffice.”) Truly the author’s family (elderly parents) serves as a mirror reflecting the ongoing events, but also offers a retrospective reflection of Jewish lot in Bosnia and Yugoslavia during the Second World War and beyond. The environment where the author worked, the Faculty of Philosophy, presents some sort of a mirror too. (Levinger-Goy offers only the first names of people, no surnames and sometimes even only the profession of those she mentions in the text.)

She renders in italics everything that refers to the periods outside the one described (1992-2002) defining clearly each specific period: in Sarajevo, in Belgrade, in Britain (London and Cambridge). There is also a description of a place called Pirovac at the Croatian coast, where the family had a short break upon leaving Sarajevo, at the end of the summer of 1992. They travelled in a convoy, of course. With so many adversities on the way. She also exhibits her need to care for others, not only her parents. (She had never turned to anybody for help for herself.)

This book would have never been written had Jasna Levinger-Goy turned down an invitation for a drink by one of her friends, a painter. Without her book we might have never asked the question: “did every shelter (and not only in Sarajevo) have its own story?” When she walked into the pub to accept the drink the shell fell exactly at the spot she would have been at had she not entered the pub. And it is not the only detail that would remind all the older readers (and not only those from Sarajevo or Mostar) who were unlucky enough to have experienced the war that a chance could be both lucky and fatal.

Yes, this is the book of many a detail. I realised that having read it twice. I often found myself feeling uncomfortable while asking myself the very same questions Jasna Levinger-Goy poses within her testimony.

I, as a reader familiar with the misery of the recent history there (1990-2023), as God is my witness, often remembered some details I believed had vanished for ever. Above all I remembered the letters friends and family were sending – those who remained in the hell that the war created, as well as those who left one way or another. I am unable to choose the best detail. Maybe the one where the author describes the time in Belgrade when among all the humanitarian gifts she received a bouquet of flowers? A true symbol of human dignity which serves as a proof that the sense of beauty was still alive. Or maybe, while I was reading – probably with unbearable lightness? – about the death of her husband Edward Dennis Goy (a well-known Slavist and translator who had to take early retirement from teaching Yugoslav Studies at Cambridge University due to the disappearance of Yugoslavia, but then married a Yugoslav.) It brought back the remark by Andrić, upon the loss of his wife: “Now, that all my good has died…”

Now I seek forgiveness from those objecting to my frequent digressions but I have to say that I jotted down at the end of this book a remark: Pascal’s reed.

A philosopher from the time past yet our contemporary who in his search for meaning emphasised dignity and wrote: “Man is only a reed, the weakest in nature, but he is a thinking reed. There is no need for the whole universe to take up arms to crush him: a vapour, a drop of water is enough to kill him, but even if the universe were to crush him, man would still be nobler than his slayer, because he knows that he is dying and the advantage the universe has over him. The universe knows none of this.”

Link for review as originally posted in Italian:

https://www.balcanicaucaso.org/aree/Bosnia-Erzegovina/Jasna-Levinger-Goy-la-storia-di-un-ex-jugoslava-225440

https://radiogornjigrad.wordpress.com/2023/06/10/knjiga-britanske-sekularne-jevrejke-jugoslavenskog-porijekla/

5.0 out of 5 stars: A Woman Under Siege

Robert Neil Smith, Amazon Reviewer March 2023

In spring 1992, Jasna Levinger-Goy, a university lecturer became increasingly baffled by ethnic tensions in her hometown of Sarajevo that accelerated into a full-blown civil war. She lived through the hell of snipers and shelling before escaping to Belgrade then London and Cambridge, where she now lives. Out of the Siege of Sarajevo is the poignant and illuminating memoir of a woman searching for her lost identity.

Levinger-Goy begins with a necessary overview of Sarajevo and her life in it before the civil war. While she saw the signs of that impending conflict, Levinger-Goy lived in denial, despite, or perhaps because of, her education and position as a professor. Then the shelling started, and she found herself having to survive amidst decreasing supplies and increasing danger. To her horror and bewilderment, Levinger-Goy came to accept that Sarajevo was under siege and the atrocities were piling up. Hunger and deprivation came with the shells, but Levinger-Goy, her family, and neighbours learned to survive. She describes her powerlessness and the randomness of death by shellfire or sniper bullet as she walked around town looking for milk and other supplies. She became a regular visitor to the local Jewish Community centre and people she knew dropped by her house just to talk. Finally, Levinger-Goy knew the time had come for her to leave. This was an ordeal in itself, but she found time to arrange a marriage with a man she was trying to help get out of the city. Then, in August 1992, Levinger-Goy boarded a bus with her parents and left.

After a harrowing bus journey, the family arrived in Pirovac where they could recuperate, and from there, they travelled to Belgrade. Settling down in a new city was not easy for a refugee, but Levinger-Goy kept going, finding work and fitting in as best she could in her desire to feel ‘normal’. Even though the complications continued, Levinger-Goy resumed her academic interests and things seemed to be going well. But all around her, the economy was collapsing, and refugees were scapegoated, yet she could not go back to Sarajevo. Levinger-Goy chose the UK, and she emigrated with her mother three years after the war came to Sarajevo. The settling in process began again, this time more successfully, though not without its obstacles. Levinger-Goy married a UK citizen and moved to Cambridge. When her husband died in 2000, she lapsed into depression from which she struggled to recover. Levinger-Goy finally returned to Sarajevo in 2004 but met with resentment and hatred for leaving; she has never gone back. Her memoir closes with an addendum on Yugoslavia in WWII, an update on all the people she mentions in the book, and an excerpt from a short story that illustrates some of the issues that linger in Sarajevo.

Memoirs are difficult to review because you are challenging the writer’s lived experiences. When they fail, they do so usually for fabrication, grandstanding, or too many errors. Sometimes, they are just boring. Levinger-Goy’s memoir is none of those. This is a well-written and touching account of a woman’s struggle to comprehend her ordeals, first under fire in Sarajevo then as a refugee. With Europe roiled once more by war and a seemingly constant refugee crisis, memoirs such as these are important guides to understanding. Only a monster could read this and not feel compassion for Levinger-Goy and those like her who have faced the worst humanity has to offer yet show resilience and fortitude in trying to rebuild their lives.

This is a well-written and touching account of a woman’s struggle to comprehend her ordeals, first under fire in Sarajevo then as a refugee.

Beating Tsundoku

Read the Full Review Here

Starting with the choice of the title itself - Out of the Siege of Sarajevo: Memoirs of a Former Yugoslav - Jasna Levinger-Goy’s book stands out from the multitude of the works dealing with Bosnian war, works by various both domestic and foreign participants, witnesses and commentators, which for the past quarter of a century have flooded the market. Having defined herself as ethnically Yugoslav at the outset she distances herself from siding with any warring party and voluntarily accepts the role of an outcast which gives her narrative authentic and convincing slant. And as a consequence of siding with those who probably have lost most in that war, the central theme of the book revolves around the search for a new identity. It is the search imposed upon a former Yugoslav who was forcefully and cruelly deprived of a chance to trust her ability to overcome the effects of various divisions in Bosnian as well as other hellholes. Hence the memory of a tragic yet confined historic conflict turns into a bitter drama of a modern individual attempting to restore the sense of personal dignity and humanity.

Bogdan Rakić, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana

I have read your book. I read it almost in one go driven by the amount of interest it engendered, from its first to the very last sentence.

Aleksandar Gaon, journalist, Belgrade

My first impression is that your book is so very different from many others written on the subject of the war in and around Sarajevo. I read some of those. I’d define your book as the narrative “from within”; the recent distressing history as seen through the eyes of an immediate witness. And that was the reason I was compelled to keep on reading. You are showing us two sides; the town immersed in evil on one side and the struggle of your family and yourself on the other. An escapade in which it was hard to avoid death. Almost like one of Dante’s inferno circles into which the innocent people were crammed.

……

I was not born in Sarajevo, neither had I ever lived there but I had spent quite a lot of time there either visiting friends or pursuing my journalistic career. I even spent my military service in a Sarajevo barracks. So Sarajevo became very familiar. Your text, with the images it conjured up for me, took me back to the familiar streets, those I used to know and, why not admit it, I came to like. It was an awful feeling to find myself suddenly putting my erstwhile experience alongside the events you had described. However, I had no choice but to walk with your book up and down the town enveloped in hatred. … Yet the country in which we were growing up was not marred by hatred.

When Jasna first came to Belgrade from the hell that Sarajevo had turned into, I met her and we talked and talked a lot. She was telling me about the things she had gone through, she described all the aspects of her life of desperation. Listening to her I thought to myself: “God what a novel that is! This has to be written down.” In those days her words exuded anguish and fear; very little hope or sober thinking.

Dejan Čavić, actor, author, translator; at the Belgrade book launch

And I remember the day when (the English edition of) Jasna’s book arrived. The dedication read:

“Dear Dejan and Goca, I hope that you will enjoy my memoir and I hope that it won’t upset you too much. Love, Jasna”

It did upset us, it upset us a lot. As soon as I received the book I read it straightaway, I devoured it. I was both dazed and very impressed because that book was an impressive book.

Everything described in this book presents a sort of “purification” and it also demonstrates the need to name and leave behind (on paper) everything evil, while turning towards life ahead which could not possibly be worse than the one lived at the time. The message of the book is that some light at the end of the tunnel is bound exist. Eventually there is the realisation that light does exist and the light affirms how magnificent life is.

Vule Žurić, writer, at the book launch in Belgrade

The author sincerely describes the events whilst avoiding all the traps that memory poses. She presents events without evaluating them either against the standards of the current moment or through the knowledge and experience she has acquired in the meantime. To me that is one of the main values of this book. Those who accept that way of reading and understanding it might find in it a valuable reference in interpreting the times we live in.

Maša Miloradović, Librarian, The National library of Serbia, Belgrade

I have just finished reading your book entitled “Iz opsednutog Sarajeva” (literal translation: “Out of the obsessed/haunted Sarajevo”) and to my mind the title is a very good choice because of its ambiguity. Sarajevo at the time was neither besieged nor trapped, rather it was obsessed and crazy; it was overwhelmed by lunacy. Rational judgement was absent. The sense of beautiful and good, of friendly and of life in general did not exist; every meaning of life was completely lost. Sarajevo was an obsessed town. Everything described is a wonderfully presented true life or “žitije“ as those of the Orthodox religion refer to it. I found all of it extremely exciting and moving. Your writing is multi-layered and presents the circumstances step by step, interspersing chronology with comments from the present. You have achieved a realisation of the “view from above” which completes the narration. There is no remorse, no regrets, no torment on your part in the book.

Rada Stanarević, Retired Literature Professor, German Department, Belgrade University, Serbia

………

There is so much in here, in this book of yours. A treasure trove! The story is told through many details enveloped in the painful emotions from which they emanate. And the story keeps giving as if there were no end to it.

It is going to become a classic – and I don’t mean ‘a minor classic’, for the seamless weave of historical and personal is uniquely powerful. You remember one of the first titles, ‘Who Do You Hate?’? Well, that all-pervading sense of hatred comes over very strong, and in a way that will be the most important message of the book, it seems to me: it was this visceral hatred, such as we haven’t seen in this country for hundreds of years, that messed your life up for you and so many others; not that life under Socialism was fun either. I’m so glad that it is going to appear in Serbia. … But I think it will percolate over here, too – a succès d’estime that will get through. It usually takes ten years or so, in my experience! All one can do is spread copies about.

Dr Patrick Miles, writer-Slavist

Reading your wartime memoir against the backdrop of the current conflict in Ukraine is an eerie experience.

Yechiel Bar-Chaim, Country director for the former Yugoslavia for the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee during the war in Bosnia

It’s not exactly a civil war there, although, judging from what is happening here between the UA refugees, the tensions between Russian-speaking and Ukrainian-speaking refugees do reflect a sharp internal fault line. As you make clear, the sudden collapse of trusted ties is one of the most devastating consequences of this kind of conflict.

……….

In your memoir empathy and simple human kindness stand out as the traits we all need to show for each other. I will keep that counsel in mind.

Many thanks for writing your story which brought back such an abundance of half-forgotten memories.

One rarely comes across those authors who offer their own life story yet who manage to suppress the onrush of emotions; those who soberly explore the traumas and injustices while not dwelling on grudges and deprivations. The book spontaneously offers a combination of charm and stoicism. The linguist Jasna Levinger-Goy describes the sacrifices she has made in dangerous situations as well as those good deeds that come her way unexpectedly in moments of utter hopelessness. Both bitterness and pain vanish through rational analysis but the gamut of complex and contradictory emotions does not disappear. The subtitle “Memoir of a Former Yugoslav” itself uncovers a myriad of emotions and bewilderments. In this autobiography gratitude to others is always in the forefront. Determined to stay in war-torn Sarajevo with her parents, the author incessantly challenges and analyses herself: “It was reckless not to register the new upside-down world”. “Distrust, hatred, starvation and ultimately the real threat of death” turn her into an unfamiliar self, into one she is puzzled by. War inevitably destroys trust and meaning, it destroys identities, pushes even the most honourable ones into dangerous and humiliating situations. To suggest to a Yugoslav that Israel is her spare homeland, to find oneself buying five kilos of mustard when there is nothing else to buy, or to pay a high price in Deutsch Marks to a doctor turned butcher for a small piece of beef are all fragments of the cruel nightmares the author is unable to leave behind even while living a happy life.

Prof Vladislava Gordić Petković, professor of literature at the Department of English Language and Literature at Novi Sad University (Serbia)

Newspaper article: https://nova.rs/kultura/kad-lekar-postane-mesar-a-ostavljene-zene-jede-vreme-lektira-za-ovu-nedelju/

What I appreciate about [this] book is the reality [the author] portrays beyond leaving Sarajevo. I work with a Lebanese nonprofit, so I'm aware that people can often assume life goes on as usual once someone has left the city that's caused them so much pain and suffering. But [this] book outlines so perfectly how, for many refugees and forced emigrants, the challenges upon leaving can be just as difficult as staying -- only in very different ways.

Lara Guest

This book offers a raw and honest account of the experience of being caught up in the ravages of brutal hostilities that took place in the centre of modern day Europe. Jasna Levinger-Goy bravely recounts her experiences of her life as a ‘Yugoslavian’ caught up in the Bosnia and Herzegovina civil war, between 1992 and 1995. The author skillfully captures in words her reslience, defiance, despair and will to navigate not only her own survival but that of her terminally ill father and her aging mother, as the civil society she has always known breaks down around her. The book not only gives the reader insight into what people have to endure to survive when war comes to their door, but it is also an exploration of identity and why it is so important to us as human beings. The author laments the loss of her Yugoslavian identity which can never be recovered, but through her experiences of survival she discovers and connects to her dormant Jewish identity. The book is a rush of pain, anguish, anxiety, fear, loss, love, introspection and renewal. This is a piece of European history that must not be forgotten and we owe sincere thanks to the author for bringing it to us with such clarity. This is an important book and a gem of a read.

Debra Brunner; Co-founder and CEO - The Together Plan, UK Charity

Review as featured in

History of War

About Jasna Levinger-Goy

JASNA LEVINGER-GOY was born in Sarajevo, former Yugoslavia. She has a BA in English Language and Literature from Sarajevo University, an MA in Linguistics from Georgetown University, Washington DC, and a PhD, also in Linguistics, from Zagreb University. In the former Yugoslavia she was a university lecturer at Sarajevo University and later at Novi Sad University. In the UK she was a lector in Serbo-Croat at SSEES, University College London and a tutor in interpreting at London Metropolitan University. She has published a number of articles and translations both in Serbo-Croat and in English. While in Sarajevo she translated Emily Dickinson’s poetry in cooperation with Marko Vešović, published by Svjetlost Sarajevo in 1989 and by OKF Cetinje in 2014.

She moved to the UK during the Bosnian civil war and married Edward Dennis Goy, a Cambridge University Slavist. They worked together on various translations, including translations into English of the Yugoslav novels, The Fortress by Meša Selimović and The Banquet in Blitva by Miroslav Krleža. In the early 2000s she qualified as an integral psychotherapist and has her own practice in Cambridge.