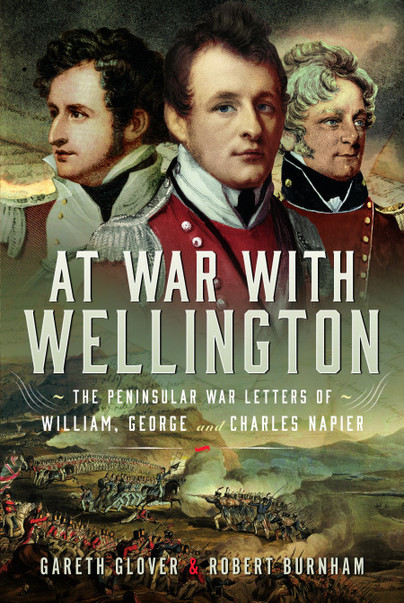

At War With Wellington (Hardback)

The Peninsular War Letters of William, George and Charles Napier

(click here for international delivery rates)

Order within the next 7 hours, 49 minutes to get your order processed the next working day!

Need a currency converter? Check XE.com for live rates

| Other formats available - Buy the Hardback and get the eBook for £1.99! | Price |

|---|---|

| At War With Wellington ePub (6.1 MB) Add to Basket | £6.99 |

The Napier family are famous for their military exploits in the Peninsular War. Charles served in the 50th and 102nd Foot, George in the 52nd and 71st Foot and William (the famous historian of the Peninsular War) who served with the 43rd Foot. Two or three of them were always serving in the Peninsula at any given time and all suffered a number of severe wounds.

William has a basic biography written of him and his famous History of the Peninsular War is littered with his personal and professional prejudices; Charles wrote a form of autobiography, mostly dealing with his later India campaigns; and virtually nothing has been written on poor George, despite the fact that he commanded the storming party at Ciudad Rodrigo, where he was severely wounded. However, much of this writing emanates from decades after they fought, when memories and changing political attitudes had clearly affected their writing.

At War With Wellington focuses on their private letters penned immediately from the front, without that dreaded hindsight. They are packed with detail of the horrors of battle and siege warfare, but also show life in the Army, the close bond between the three brothers while serving close to each other in action and also with their mother at home, who clearly had constant fears that her three boys would never come home again. All three did survive but were all badly maimed during this war.

Their individual exploits are legion, but no one has ever brought all of this material together in one book, until now. Between them, they participated in almost every action in the six-year war and two of them participated in the Army of Occupation in France from 1815-18, although none were at the Battle of Waterloo.

Their close relationships with many senior officers of the period, gives a rare glimpse into the thinking of the generals and helps us understand how the decisions were made and with what information they were formed. Being also politically active, it is fascinating to hear their views on both political matters at home and the Allied cause against France.

This material is both absorbing and revealing. It adds much to our understanding, primarily of the Napier’s themselves, but also the effects of a world war on the family dynamics, the political upheavals surrounding it, the failures of the Allied campaigns and even the perceived failings of the senior officers in their promotion of the war effort, which are expressed vehemently.

At War With Wellington opens a window onto a different view of the war, from very experienced soldiers, but with very different political leanings, and will cause readers to question some of their long-held views.

Subtitled The Peninsular War Letters of William, George and Charles Napier, this book contains extracts from the original private letters and journals of the three Napier brothers and those of fellow officers, written while they were on campaign, without the distortion of hindsight that affects later writings.

Arthur Harman, Miniature Wargames

All three bothers served with distinction in the Peninsular War and were wounded on active service.

Charles, the oldest, was commissioned an ensign in the 33rd Foot in January 1794 and became a lieutenant in the 89th Foot in May of the same year, aged eleven! In May 1806 he was promoted to a majority in the Cape Corps, from which he exchanged into the 50th Foot, which he commanded at Corunna, being wounded five times and taken prisoner. After being exchanged in January 1810, he served as a volunteer in the Light Brigade, was aide de camp to General Craufurd at the Coa and was then attached to Wellington’s staff. At Busaco he was shot in the face, his jaw broken and his eye injured. He was also engaged at Fuentes de Onoro and the second siege of Badajoz. Later he commanded a brigade in the American War of 1812.

George was appointed a cornet in the 24th Light Dragoons in January 1800, aged fifteen, and became a lieutenant in the 46th Foot in June of the same year. After a period on half pay. He transferred into the 52nd Foot in 1803 and became a captain in 1806. He served under Sir John Moore at Shornecliffe, Sicily and Sweden and was one of his aides de camp at Corunna. He continued to serve in the 52nd Foot in the campaigns of 1809 to 1811, was slightly wounded at Busaco and, then a major, lost his right arm whilst commanding the storming party of the Light Division at Ciudad Rodrigo in January 1812. He rejoined the 52nd at Jean de Luz early in 1814 and was present at the battles of Orthez, Tarbes and Toulouse.

William received a commission as ensign in the Royal Irish Artillery in June 1800, but soon transferred to the 62nd Foot, being promoted lieutenant in April 1801. When the war resumed in 1803 Sir John Moore suggested he should join one of his light regiments, and after a series of transfers he became a captain in the 43rd Foot in August 1804. He served in the Corunna campaign and returned to Portugal in May 1809, was wounded in the left hip at the Coa, was in the actions of Pombal and Redinha, and was dangerously wounded by a bullet in the spine at Casal Nova in March 1811. He was appointed brigade-major to the First Brigade of the Light Division, took part in Fuentes de Onoro and the second siege of Badajoz. After recovering from fever in England, he rejoined the army in May 1812, taking command of the 43rd as a regimental major - the lieutenant colonel having been killed in the siege – at Salamanca, and again at the battle of the Nivelle when the colonel fell sick, where the 43rd stormed La Rhune. William was twice wounded at the battle of the Nive, was promoted brevet lieutenant colonel in November 1813 and was present at Orthez, but his wounds then compelled him to return to England.

The editors, both highly respected researchers of the Napoleonic Wars whose names will be familiar to many readers, have judiciously pruned the material, omitting discussion of purely family affairs, complaints about financial issues and remarks on the political situation in both Britain and Europe, to focus upon their military lives; their experiences on campaign and in battle; their views on the current military situation; and their comments on their commanders, fellow officers, men and allies.

The text ends with a very brief chapter giving details of the brothers’ later military careers, lives and deaths.

Thirteen pages of endnotes, a short bibliography listing the biographical works about his brothers by William Napier, Charles Napier’s autobiography, and later biographies of William and George, and an index conclude the book.

It is a great pity that the colour portraits of the three brothers in their regimental uniforms appear only on the dustjacket, rather than among the colour plates inside the book, and that there is no note thereon explaining clearly which brother is depicted in each portrait. The portraits are, from left to right, William, George and Charles, in the same order as their names on the cover, but readers making the brothers’ acquaintance for the first time might not realise that.

The book contains two sections of plates: the first, eight pages of monochrome reproductions of drawings of places in the Peninsula, Bermuda and North America, are presumably by Charles who served there, though this is not stated. A further eight pages of colour reproductions of Peninsular scenes and costumes, together with some Native Americans, would seem to be by the same hand; again, there is no attribution.

If like me, you enjoy reading the letters, diaries and memoirs of British officers who served in the Peninsula, you will definitely enjoy this book. The exploits of the Napiers also offer many ideas for recreating the battlefield behaviour and contemporary attitudes of British officers in tabletop skirmishes, using rules such as Sharp Practice, or in roleplaying games. May all your lead or plastic officers serve so well and so bravely in your miniature battles!

About Robert Burnham

ROBERT BURNHAM, a retired army officer, has written scores of articles and numerous books on the Napoleonic Wars. He has recently stepped down after twenty-two years as the editor of the Napoleon Series, a fascinating and all-embracing website, the largest of its kind. It is a ‘must’ for anyone interested in the Napoleonic era. It can be accessed at: www.napoleon-series.org

About Gareth Glover

Gareth Glover is a former Royal Navy officer and military historian who has made a special study of the Napoleonic Wars for the last thirty years. In addition to writing many articles on aspects of the subject in magazines and journals, his books include From Corunna to Waterloo, Eyewitness to the Peninsular War and the Battle of Waterloo, An Eloquent Soldier, fourteen volumes of The Waterloo Archive, Waterloo: Myth and Reality, The Forgotten War Against Napoleon: Conflict in the Mediterranean 1793-1815, The Two Battles of Copenhagen 1801 and 1807: Britain and Denmark in the Napoleonic Wars and Marching, Fighting, Dying: Experiences of Soldiers in the Peninsular War.

Sharpe and his adventures has made the 95th Foot renowned again and the discovery of an unpublished diary by an American from Charleston South Carolina who served, despite his father’s objections, as an officer in this elite regiment has caused great excitement. James Penman Gairdner was born in Charleston, South Carolina, but he was sent back to the ‘Old Country’ for his education, receiving his schooling at Harrow. After school, rather than joining his father’s merchant business he decided to become a soldier, receiving a commission in the famous 95th Rifles. He subsequently served,…

By Gareth GloverClick here to buy both titles for £54.99