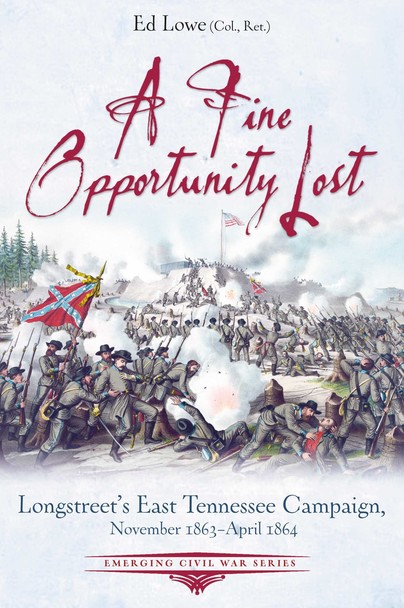

A Fine Opportunity Lost (Paperback)

Longstreet’s East Tennessee Campaign, November 1863 – April 1864

Imprint: Savas Beatie

Pages: 192

Illustrations: 75 images, 10 maps

ISBN: 9781611216738

Published: 15th December 2023

(click here for international delivery rates)

Order within the next 7 hours, 8 minutes to get your order processed the next working day!

Need a currency converter? Check XE.com for live rates

Lieutenant General James Longstreet’s deployment to East Tennessee promised a chance to shine. The commander of the First Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia had long been overshadowed by his commander, Robert E. Lee, and the now-martyred Second Corp commander, Stonewall Jackson. Lee had nonetheless leaned heavily on Longstreet, whom he called his “Old Warhorse.” Reassigned to the Western Theater because of sliding fortunes there, the Old Warhorse hoped to run free with—finally—an independent command of his own. This experience is depicted in A Fine Opportunity Lost: Longstreet’s East Tennessee Campaign, November 1863 – April 1864 by Ed Lowe (Col., Ret.) For his Union opponent, Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside, East Tennessee offered an opportunity for redemption. Burnside’s early war success had been overshadowed by his disastrous turn at the head of the Army of the Potomac, where he suffered a dramatically lopsided loss at the battle of Fredericksburg followed by the humiliation of “The Mud March.” Removed from army command and shuffled to a less prominent theater, Burnside suddenly found his quiet corner of the war getting noisy and worrisome. The mid-September loss by the Union Army of the Cumberland at the battle of Chickamauga left it besieged in Chattanooga, Tennessee. That, in turn, opened the door to Union-leaning East Tennessee and imperiled Burnside’s isolated force around Knoxville, the region’s most important city. A strong move by Confederates would create political turmoil for Federal forces and cut off Burnside’s ability to come to Chattanooga’s aid.Into that breach marched Longstreet, fresh off his tide-turning role in the Confederate victory at Chickamauga. The Old Warhorse finally had the independent command he had longed for and an opportunity to capitalize on the momentum he had helped create. Longstreet’s First Corps and Burnside’s IX Corps had shared battlefields at Second Manassas, South Mountain, Antietam, and Fredericksburg. Unexpectedly, these two old foes from the Eastern Theater now found themselves transplanted in the Western—familiar adversaries on unfamiliar ground. The fate of East Tennessee hung in the balance, and the reputations of the commanders would be won or lost.

After disagreeing with Robert E. Lee about the strategy and tactics employed in the campaign and battle of Gettysburg, Lieutenant General James Longstreet had agreed to move his First Corps from the Army of Northern Virginia to join Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee, arriving on September 19th, 1863, the second day of the battle of Chickamauga. Appointed Bragg’s Left Wing commander, Longstreet helped win a stunning victory over Rosecran’s Army of the Cumberland the next day.

Miniature Wargames

But after the battle, Longstreet’s relationship with Bragg deteriorated and the latter was angered by his new subordinate’s failure to prevent the capture of Brown’s Ferry or to disrupt the establishment of the Federal ‘Cracker Line’ supply route at the battle of Wauhatchie on October 29th.

This volume in the Emerging Civil War series examines the campaign conducted by Longstreet when Bragg decided to send him and his two divisions to operate against Major General Ambrose E. Burnside’s Army of the Ohio at Knoxville, gambling that Longstreet could retake Knoxville and return to Chattanooga in time to fight Grant, reinforced by Sherman’s Army of the Tennesssee.

Modern maps depict Grant’s ‘Cracker Line’; the Battle of Wauhatchie; the movements of Burnside’s and Longstreet’s forces to Knoxville; the engagement of Campbell’s Station on November 16th, 1863, and Burnside’s withdrawal towards Knoxville; the defences of Knoxvile and Longstreet’s attacks on November 29th; a more detailed depiction of the Confederate attacks on Fort Sanders on that date; and Longstreet in East Tennessee, showing the locations of engagements fought between November 1863 and January 1864.

The book is profusely illustrated with numerous small reproductions of contemporary portrait photographs of officers of both sides, accompanied by brief biographical details, in the margins beside the text. There are also contemporary and modern photographs of places mentioned in the text, reproductions paintings and prints of battle scenes and modern photographs of memorials and commemorative plaques.

There are three appendices. Civil War Knoxville and the Loss of Fort Sanders by Jim Doncaster describes the changes that have occurred in the city and its environs since the Civil War, and contains photographs of surviving buildings that would be very useful if visiting the city.

James Longstreet and the Army of Tennessee’s High Command by Cecily Nelson Zander explains how Longstreet’s arrival ‘irrevocably changed the dynamic in Bragg’s army’ and how he became ‘the de facto leader of the anti-Bragg faction’.

Longstreet and Confederate Strategy by Ed Lowe discusses ‘Longstreet’s strategic thinking, looking beyond his own area of operations’.

The book concludes with Orders of Battle for the Knoxville Campaign, with the names of brigade commanders and list of their regiments but without even approximate strengths of any formations, and two pages of Suggested Reading. There is no index.

A thoroughly researched introduction to a campaign that will be unfamiliar to many American Civil War gamers, that offers two battles and an attack upon an earthwork fort which could quite easily be used as interesting scenarios for wargames in which the players would not be greatly influenced by hindsight.