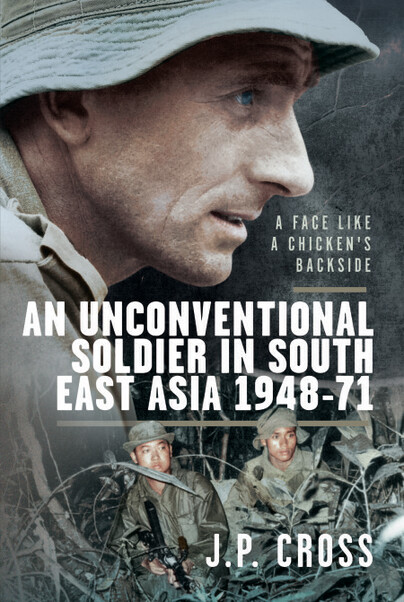

A Face Like a Chicken's Backside (ePub)

An Unconventional Soldier in South East Asia, 1948–71

File Size: 6.7 MB (.epub)

Pages: 224

Illustrations: 16 pages b&w plates

ISBN: 9781036150099

Published: 6th November 2024

| Other formats available | Price |

|---|---|

| A Face Like a Chicken's Backside Hardback Add to Basket | £25.00 |

In almost forty years in Asia without a home posting, British officer John Cross spent ten of them ‘under the jungle canopy’. He amassed a wealth of experience fighting against Communist Revolutionary Warfare, and training others to do so. As a result he was called upon to work in many formidable situations, and twice found himself on an army short-list of one for difficult tasks.

Cross focuses on five stages in his extraordinary army career. He spent eight years as a company commander with the Gurkhas in Malaya fighting jungle operations against the communists. After that he took part in the attempt to end twenty years of guerrilla domination over the aborigines in north Malaya, and secured the territory between Thailand and the aboriginal population that had been occupied and used by the guerrillas.

As commander of the Sarawak and Sabah Border Scouts in Borneo, Cross was constantly on the move. At one point in this hectic period in his service he narrowly escaped having his head cut off by an angry tribesman. He then commanded the Gurkha Independent Parachute Company, which had to operate like paras, SAS men and conventional soldiers, during the latter part of the Indonesian Confrontation with Malaya.

Finally, Cross was the last commander of the British Army’s Jungle Warfare School, which trained officers and men from five continents – including American trackers who, as a result, had the price on their heads doubled in Vietnam.

After the closure of the Jungle Warfare School, John Cross was asked to work in both the Royal Thai Army and the Army of the Republic of Vietnam. Instead he became Defence Attaché in Laos.

This fascinating book provides vivid insight into the realities of jungle warfare by one of its most experienced practitioners.

This autobiography of the military service of legendary Gurkha soldier, John Cross, now one hundred and living in Nepal, is a reprint of a first edition in 1996, a second edition in 2015/16, and now there is this third edition. This is a tribute to the interest in Cross’s life and career as a soldier, spanning forty years, mostly in Southeast Asia and the Far East, through which Cross not only acquired an impressive command of local languages, but he also led at the Jungle Warfare School in Malaya, and concluded with service in the 1970s as British defence attaché in Laos. Three strands tie together the book: the Gurkhas, Cross’s unconventional approach to soldiering, and his service in the jungle. Much of Cross’s time was in the primary forest and, with it, the smells, sounds, light, colour, animals, and aboriginal peoples. Cross’s jungle has spiritual, magical energy, and the people of the jungle, whose languages he learns to speak, drew him farther into the deep jungle. Continuous existence in the jungle and patrolling for the enemy left Cross physically debilitated. He worked closely with the Temiar jungle people as a local loyalist force in the fight against communist insurgents during the Malayan Emergency.

Matthew Hughes, Brunel, University of London

The book is in four parts: patrolling as a subaltern in the early stages of the Malayan Emergency in the 1950s, working with aboriginal peoples in Malaya in the early 1960s, leading the Border Scouts force of local Dayak on Borneo during Confrontation with Indonesia in 1963, and a final section of memoir after Confrontation on his work with the Gurkha Independent Parachute Company and at the Malaya-based Jungle Warfare School (JWS). Cross finished at JWS in 1971, after which he went to the British embassy in Vientiane. The last section is interesting as Cross’s work with Thai and Vietnamese soldiers training for jungle fighting pulls the reader into Cross’s part in the wider war against communism across Southeast Asia. Cross emerges from the text as a maverick, who from his earliest days in the Army preferred the difference of Asia to the sameness of Britain. The British Army required, in Cross’s view, ‘conformity in her children.’ Cross was not a conformist but a military adventurer. The rigours of life away on patrol in Malaya in the early 1950s drove away his fiancée, Jane, after which he devoted himself to being the best and getting the best from his Gurkha riflemen. The book has wonderful insights on the reality of active service: not just firefights in which weapons jammed, but errant moments, as when one officer tried to join the insurgents. Cross is strong on the human story of service in East Asia. As he surged forward in one attack, he saw that one of his Gurkhas had bloodshot eyes: ‘the lust to kill was in him.’

Cross could be sharp with his superiors, telling one brigadier that his rank was the most ‘useless’ in the Army. When asked why, Cross replied: ‘Because, sir, you are not near enough ground level to influence the fighting nor are you near enough the top to influence the planning.’ The inferior quality of equipment in the early days is striking: the lack of canvas boots, poor water bottles, clunky webbing, and weapons unsuitable for jungle fighting. Helicopters arrived in numbers during the Malayan conflict, and Cross brings to the fore their impact on tactical movement, but he also raises the poor quality of close-air support – both in terms of accuracy and impact on insurgent areas – with planes vectored in by crude balloons sent up by his men, not least as the heavy radios often did not work. (Indeed, radios failed to work in Afghanistan more recently, forcing soldiers there to use their mobile phones.) Cross’s record of photographing and fingerprinting dead insurgents is an interesting contrast to Dan Poole’s recent book on headhunting in Malaya during the Emergency, with its accounts of heads brought in of decapitated terrorists. There was also the friction of liaison work with the police, notably Malaya’s Special Branch. This is a useful window onto the significance of police-military relations during counterinsurgency. The tension between the two branches re-emerged during Cross’s time on Borneo. Was he a policeman or a soldier (and, indeed, who would be paying his pension)?

Cross’s book is a tremendous read and to be recommended. It is one of a number of books by Cross on his life as a soldier, and with the Gurkhas. The jungle was an exhausting environment in which to fight – this is clear from Cross’s book – but it was also a peculiar place that could work for soldiers, if they know what to do, how to fight, how to live in the jungle. Cross dedicated his career to making jungle life second nature for soldiers, as this book proves.

About J P Cross

In 1970, The Economist described J P Cross as ‘one of those gifted, dedicated eccentrics that the British Army has the habit of spawning.’ In his career spanning 40 years, Colonel Cross commanded a rifle company during the Malayan Emergency and the Border Scouts in Borneo, directed the British Army Jungle Warfare School and recruited Gurkhas for the British Army in Nepal.